Dutyholders, employers, or premises owners have a duty of care under health and safety law to protect users of their water systems. Today we will discuss the importance of a hot water risk assessment and the importance of controlling temperatures on a healthcare site.

A hospital or other healthcare buildings such as a GP surgery or care home need to be particularly diligent when it comes to managing the potential risks associated with their water systems. These sites are often densely populated and have many at-risk individuals who may be at risk from hot water.

Hot Water Risk Assessment

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 require employers to put in place arrangements to control health and safety risks, which includes the assessment of risk from work activities.

The HSE’s information sheet HSIS6 states “You should assess the potential scalding and burning risks” and “ a risk assessment of the premises should be carried out to identify what controls are necessary and how systems will be managed and maintained”.

Unfortunately, controlling the risk from hot water is not as simple as reducing the water temperature, as the risk from Legionella bacteria will also need to be assessed, as stated in the HSE’s ACoP L8. The result of a Legionella risk assessment may require the duty holder to maintain their hot water systems at a temperature that represents a scald risk (above 44°C [HSIS6]), this is because the traditional control strategy for Legionella is by using heat to kill it.

Unfortunately, controlling the risk from hot water is not as simple as reducing the water temperature, as the risk from Legionella bacteria will also need to be assessed, as stated in the HSE’s ACoP L8. The result of a Legionella risk assessment may require the duty holder to maintain their hot water systems at a temperature that represents a scald risk (above 44°C [HSIS6]), this is because the traditional control strategy for Legionella is by using heat to kill it.

Therefore, a comparative scalding risk assessment versus the risk of infection from Legionella should be undertaken.

A water safety group could be formed to help consider these risks and agree on appropriate control measures.

All outlets delivering hot water should be assessed, with particular care given to full immersion outlets such as baths and showers. Due to the potentially large number of elderly, very young, and people who may be mentally or physically disabled, high-risk outlets must be quickly identified and assessed.

A site survey should be carried out to cover all outlets onsite and this should be kept up to date considering evolving site usage. For Legionella control, hot water outlet temperatures are required to be 50°C within one minute of operation (55°C in healthcare buildings), however, temperatures above 41°C can result in scalding injuries.

How can we mitigate scalding risk?

Following the site risk assessment there are several ways you can help manage and reduce the risks associated with hot water outlets in a healthcare environment, both from scalding and Legionella bacteria.

TMVs (thermostatic mixing valves) should be considered at all outlets where there is deemed to be a significant risk of scalding. These allow the outlet temperature to be adjusted to within a more comfortable range to prevent the risk of scalding and injury.

There are three common types of TMVs available;

Type 1 – a mechanical mixing valve with or without temperature stop (i.e., manually blended);

Type 1 – a mechanical mixing valve with or without temperature stop (i.e., manually blended);- Type 2 – a thermostatic mixing valve: BS EN 1111 and or BS EN 1287;

- Type 3 – a thermostatic mixing valve with enhanced performance: HTM 04-01: Supplement, D08. These are high-performance mixing valves that are designed to operate and protect users from scalding under both high and low water pressure, temperature instability and thermal shutdown.

The Legionella risk assessment will help the Water Safety Group (WSG) consider the needs of the patient/service user and determine whether any of the above additional scalding protection devices are required. Where practicable, TMVs should be incorporated directly in the tap fitting so that the length of blended water (Legionella risk) is minimised.

Other ways to mitigate risk associated with hot water outlets include:

- Supervision by competently trained staff when bathing vulnerable patients;

- Ensuring doors to cleaning rooms are locked on wards that have children and vulnerable patients present;

- Using appropriate hot water warning stickers on outlets that are not used for hand washing;

- Using temperature-restricted, instant water heaters.

In areas such as neo-natal units and intensive care (ICU), where infection risk is at its highest, it may be suitable to install a TMV Type 1 since patients are not exposed to the hot water but can be exposed to Legionella bacteria through aerosolisation. The Legionella risk assessment should consider this and advise an appropriate course of action.

Conflict with Bacterial Growth

Installation of TMVs can increase the risk of bacterial growth due to their complexity and component make-up.

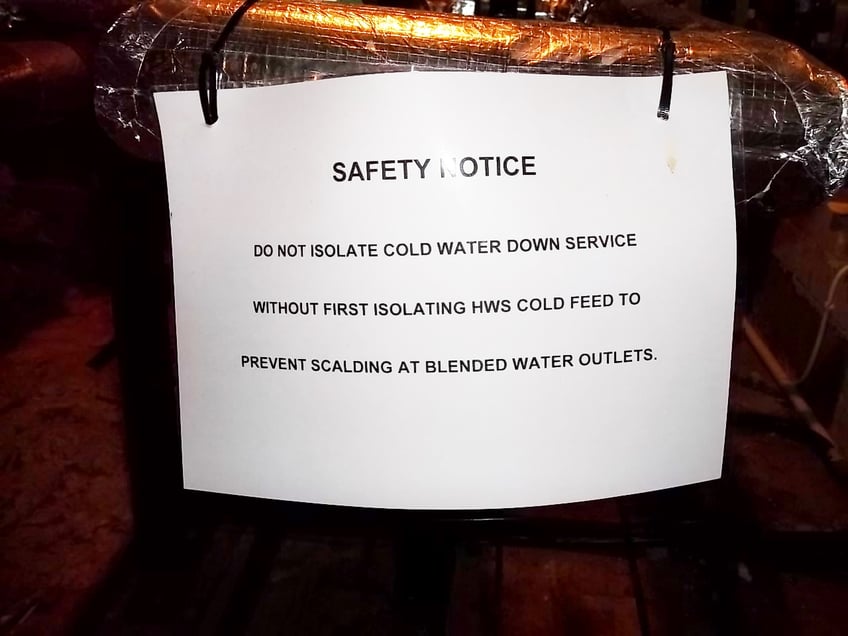

HSE’s HSG 274 Part 2 and the Department of Health’s HTM04-01 offer guidance on how TMVs should be installed to help minimise the risk from Legionella bacteria, such as;

- Installing thermostatic mixing taps to reduce the amount of blended water;

- Not fitting with spray taps;

- Fitting one TMV per outlet;

- Not fitting with flexible hose connections;

- Fitting TMV Type 1’s where appropriate;

- Installing where easily accessible for maintenance.

Whatever controls to manage the risks from hot water are chosen, they should be adequately maintained. Any defects that are reported through use or maintenance should be reported and rectified as soon as possible.

Conclusion

The dutyholder must identify all hazards that require risk assessment, which includes hot water.

Any significant risks to hot water must be reduced, whilst also considering the risk from Legionella bacteria.

Adequate controls must be put in place to reduce both hot water and Legionella risk, which may conflict however, must be agreed upon.

These control measures must be checked regularly, acted upon if failing and reviewed to ensure they are still appropriate.

Scalding from hot water is classed by the NHS as a “never event” and must be taken seriously.

Further reading> How to reduce the risk of scalding

Feel free to reach out if you have any questions about this blog or if you would like to consult with one of our experts for further advice on water hygiene.

Editors Note: The information provided in this blog is correct at the date of original publication – August 2017. (Revised November 2023)

© Water Hygiene Centre 2023