As the summer heat kicks in, it's essential to discuss something that may not be on everyone's radar: Legionella risk. You might be wondering, what’s the deal with Legionnaires’ disease during these warmer months?

To best understand the ‘summer risk,’ it’s extremely helpful to review the Legionella surveillance reports released by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) (previously Public Health England (PHE)). These reports break it down for us, summarising monthly data on reported and confirmed cases of Legionnaires’ disease.

They also provide some year-on-year comparison stats, which can help us see trends and patterns. It turns out that during those hot summer days, conditions can become just right for Legionella bacteria to thrive in water systems - think cooling towers or even decorative fountains! While you’re enjoying your summer fun, it’s a good idea to stay informed about how these risks can arise and what we can do to keep ourselves safe.

Previous Legionella Cases

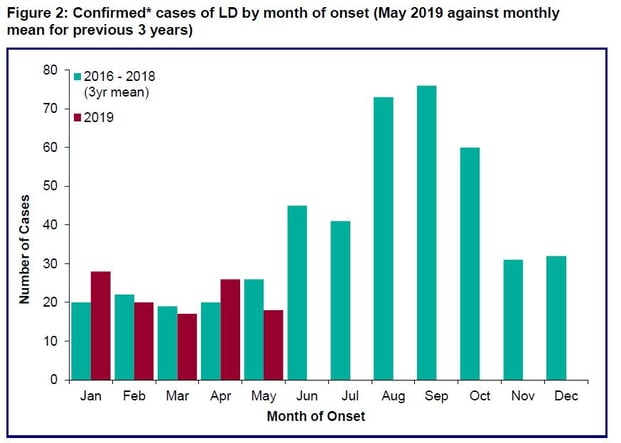

If we’re to analyse the data reported by UKHSA, then a ‘bell curve’ or ‘inverted U’ can be observed during July to November, representing an increased number of reported and confirmed cases during this period – see Figures 1 & 2 below.

Whilst Legionella bacteria live preferentially in the environment and therefore are ubiquitous within water systems (in planktonic or free-floating cell form), these bacteria may cause a problem when provided with ‘favourable growth conditions’ which are often found in man-made engineered water systems.

Moreover, when water temperatures are between 20-45˚C and the water is slow-moving or stagnant and nutrient-rich, these conditions are often precursors to biofilm formation. The architecture of a ‘mature’ biofilm is often dense and can provide good protection to microorganisms which reside within it. Following current guidance, such as ACoP L8, HSG274, and HTM04-01, can go a long way to preventing these favourable conditions when you have a robust control regime in place.

Temperature Control and Legionella

Legionella in planktonic or free-floating form are often adequately controlled with temperature (ensuring that hot water remains hot and cold water remains cold – following HSG 274 Part 2 recommendations, and HTM04-01 for Healthcare environments) but when adequate temperature control has not been achieved – leading to water temperature falling within the aforementioned ‘risk range’ (20-45˚C) and subsequent biofilm formation, then Legionella may gain greater protection from mainstay control measures such as temperature, therefore increasing the risk of waterborne infection and subsequent disease from non-compliant water systems.

How to reduce the risk of Legionella in the summer?

Turning our attention back to the ‘summer months’ of the year, compliance with water temperatures detailed within the guidance notes can sometimes be difficult, considering the impact of higher ‘ambient temperatures’ on cold water systems, which often increases the temperature of cold water supplied to premises.

Whilst this may in part help to explain the increase in Legionnaires’ disease cases throughout the warmest part of the year, we must also consider the impact of ‘holiday season’ and that a significant proportion of reported and confirmed cases of Legionnaires’ disease are reported under the ‘travel abroad’ demographic as well as ‘community acquired’.

Whilst this may in part help to explain the increase in Legionnaires’ disease cases throughout the warmest part of the year, we must also consider the impact of ‘holiday season’ and that a significant proportion of reported and confirmed cases of Legionnaires’ disease are reported under the ‘travel abroad’ demographic as well as ‘community acquired’.

It is worth noting that protocols and guidance abroad for managing the proliferation of water-borne pathogens may not be as stringent as those in the UK. Nosocomial or hospital-acquired Legionnaires’ disease is also noteworthy, as although cases from this demographic represent an overall minority, the mortality rates associated with this group are approximately three times higher compared to cases reported from non-healthcare groups, such as the community or travel (UK and abroad).

In closing, this data supports the theory that Legionnaires’ disease may affect the well and unwell alike, whether individuals travel overseas to somewhere sunny and warm, staying in hotels, villas, or apartments, or those who prefer to holiday in the UK during the summer time. Not to forget that particular concern is in high-risk populations such as those within healthcare environments, whereby predisposing factors (immunocompromise) may lead to a poorer prognosis.

Feel free to reach out if you have any questions about the issues mentioned above or if you would like to consult with one of our experts on water hygiene.

Editor's Note: The information provided in this blog is correct as of the date of original publication - July 2019. (Revised August 2025)

Image by Steve Buissinne from Pixabay

© Water Hygiene Centre 2025